A wise attorney once told me, “The road to serenity is not paved with litigation.” How true that is. Unfortunately, litigation is a familiar experience for those of us who practice medicine -- most of us will find our serenity traumatized by a lawsuit during our career. The stress can be overwhelming and even debilitating, but it doesn’t have to be. In this article we will discuss the sources of that stress and the ways to cope. I offer two common idioms to remember if you are sued for malpractice: “You are not alone,” and “You will survive.”

Fight or Flight

Physicians, like all humans, will respond to an external threat, even a non-violent threat, with a sympathetically mediated response. Although helpful in certain situations, it can be detrimental in others, especially when it involves a prolonged nonphysical threat, like the threat physicians experience when they are named in a malpractice lawsuit. Being named as a defendant in a malpractice lawsuit carries the same amount of grief and stress as the loss of a loved one.

Seeing your name on the initial complaint associated with alarming legal terms like gross negligence, below the standard of care, compensation, duty, patient injury and litigation causes a severe visceral reaction. The news that a lawsuit is forthcoming is perceived as a threat and feels like being kicked in the gut. Unfortunately, that feeling is re-experienced or may just never recede throughout the litigation process, which can take years. Just when the visceral reaction and emotions begin to settle down, they are brought right back up to the surface with the same gut-punch with every new message or document about the lawsuit. Just seeing the sender’s name on the envelope or email can cause a Pavlovian response of sorts.

Every time a physician gets a new communication from their attorney, they start to relive the case. They go over and over it in their mind. The physician begins to second-guess themselves and have self-doubt. They are told not to talk about the case by their defense attorney so they can’t even discuss it or ask a colleague or friend about it. For that reason and others, they become more isolated. They have guilt and may even experience toxic shame. In a diagnostic sense the physician is experiencing a trauma reaction, also called Malpractice Stress Syndrome. We will discuss this later.

Unfortunately, medical malpractice lawsuits are relatively common in the United States. Greater than 85 percent of physicians will face a malpractice claim during a 40-year career. The legal system is unfamiliar to physicians; it’s not our turf. We don’t know the rules, the language, the process or the procedures. We are not in charge. This is very difficult for many physicians. The good news is that almost half of malpractice claims are dropped, and another 25 percent are dismissed with no award or settlement. Overall only about 15 percent of malpractice claims are settled with a payment.

The Odds

Although not every physician sued for malpractice experiences the trauma reaction described above, studies have shown that about 95 percent of us do report significant emotional or physical reactions when named as a defendant in such a case. About 40 percent of physicians who go through the complete malpractice litigation process will experience at least one episode of a Major Depressive Disorder.

Physicians have an exaggerated sense of responsibility. We will overwork to clear our own conscience that everything has been done and done correctly. We also have an exaggerated sense of self-doubt that we missed something, so we check and recheck. These traits foster a compulsiveness that makes us good physicians but can backfire on us when we are accused and sued for malpractice. The loss or grief we feel is sometimes described as a loss of innocence.

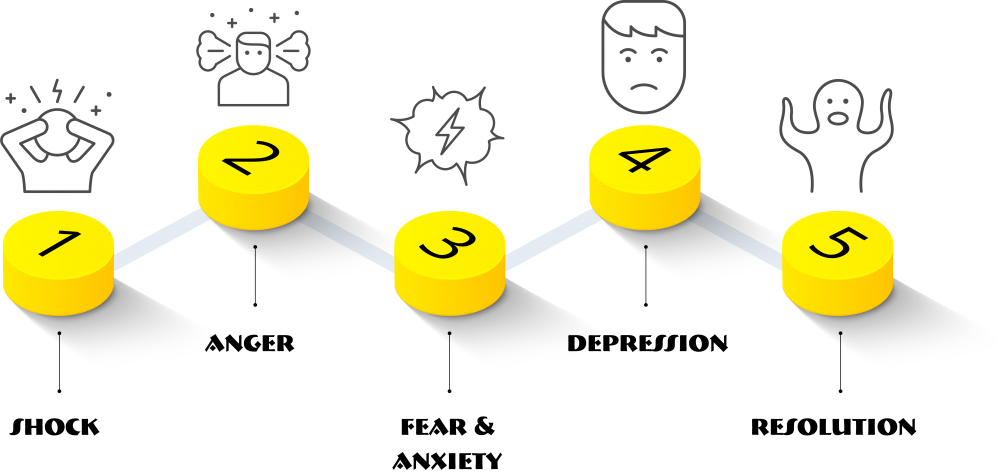

These feelings are similar in many ways to the stages of the grief reaction first described by Kübler-Ross. The emotions described below do not always happen in a serial or linear manner. The processes of a malpractice lawsuit and our processing of emotions can cause us to cycle through these phases again and again.

Grief Emotions

Shock

The initial phase of a malpractice lawsuit is called the “Service of Process.” This is when the initial Summons signed by a judge and the written Complaint prepared by the plaintiff’s attorney are delivered together to the physician defendant. When the physician defendant receives and first reads the Service of Process, they enter the Shock phase. Most physicians have difficulty comprehending what they are reading. They feel terrible seeing their name associated with such inflammatory accusations and experience the visceral reaction described above. The inflammatory wording is purposeful; it raises uncomfortable emotions the plaintiffs hope will trigger the will for a quick settlement. Other symptoms associated with this initial stage are numbness, confusion, and easy distraction. The defendant physician may make self-soothing statements such as, “It’s fine” or “I’m fine.” Many physicians get their self-identity from being a physician and for many, it’s where their self-worth is realized. They have considerable difficulty with the defendant identification. Not only is it unfamiliar, it can be denigrating. All this is made worse when it’s unexpected and the physician cannot remember the patient or the particulars of the case.

Anger

The Shock is quickly followed and often intermingled with Anger. The Anger phase is driven by frustration, resentment, embarrassment, feeling out of control, and shame. Physicians may begin to exhibit cynicism or detachment (symptoms of burnout). They may become sarcastic and irritable. Those prone to passive-aggressive behavior may start leaning more towardaggression. The physician’s self-confidence may suffer. They may begin to question their own judgment and may assume that others are questioning their judgment as well. The physician will feel betrayed and may begin to distrust their own patients.

Fear and Anxiety

The Anger phase is followed by Fear and Anxiety. Paramount in this is the fear of financial insecurity. In this phase physicians will discuss with their malpractice insurance carrier the limits of their policy. They will want to know what happens if the plaintiff wins and the amount exceeds the limits of their individual policy. They may talk with their financial planner or personal attorney to try to protect personal assets. There is also fear about what other physicians will think, and what their own patients think when they hear that their doctor was named in a malpractice lawsuit. Catastrophizing - predicting the worst possible outcome - is common in this phase, as is ruminating on the past or future – anything but the present.

Depression

Depression is generally the next phase. As mentioned previously around 40 percent of physicians who go through a malpractice lawsuit will meet the DSM-5 criteria for a Major Depressive Disorder. Many physicians will just have subclinical symptoms of Depression such as reduced energy, decreased social interest, decreased motivation, crying, and changes in constitutional habits. The Depression phase may be expressed as feelings of hopelessness or helplessness, feeling overwhelmed and disappointed. Some physicians will self-medicate with alcohol or prescription drugs which will lead to its own set of problems. Some physicians will contemplate or fantasize about suicide.

Resolution

The final emotional phase to being named as a defendant in a malpractice lawsuit is Resolution. This phase can be experienced as emotional neutrality or acceptance. If the physician does not get to this phase, then they are fighting or avoiding the reality of the malpractice lawsuit.

Resolution doesn’t mean they are not experiencing some distress – rather, it means the physician has learned how to live with or accept the malpractice lawsuit for what it is, or perhaps the malpractice lawsuit has been adjudicated and is no longer a threat. Resolution can feel like self-validation, self-compassion, wisdom, and pride. The physician was able to be vulnerable and tolerated their emotions. The physician is engaging with reality as it is and not how they want it to be.

The stop-and-go nature of litigation is foreign and frustrating to physicians. Physicians are trained to deal with a medical problem until it is resolved or at least stabilized. Malpractice litigation will begin with a tsunami of emotions when the Service of Process is received by the physician. Then there will be a decrescendo effect that may go on for months at a time when there is no activity. Another wave hits with interrogatories and depositions followed by yet another period of little activity. Every part of the litigation process triggers the emotional series. When that part of the process is completed, the emotional series may wind down as well, even to resolution. The emotional series process may dissipate a little quicker with each subsequent wave of activity, especially if the events bring promising news. Overall this is a very individualized process. With some physicians the emotional series only reaches resolution after there is a settlement or the case is closed. As you can imagine, some physicians feel like they are on an emotional roller coaster whereas other physicians just feel the high stress of the unknown.

Malpractice-Related Disorders

This emotional series of Shock, Anger, Fear/Anxiety, Depression and Resolution are experienced by most physicians named in a malpractice lawsuit. These stages are normal, just as grief is a normal emotional reaction to the loss of a loved one. However, just as grief can become complicated and lead to other disorders, the emotions caused by a malpractice lawsuit can become complicated and lead to other disorders such as Major Depressive Disorder and Trauma Related Disorders.

Depressive Disorder

As stated earlier, many physicians involved in malpractice litigation will experience a Depressive Disorder. The symptoms needed to make a diagnosis of a Major Depressive Disorder include five or more of the following criteria within a two-week period and they need to cause clinically significant distress or impairment:

Trauma

Another set of disorders that can manifest during a malpractice lawsuit are the Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders -- the classic ones being Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The symptoms of these trauma-related disorders include:

The symptoms of Acute Stress Disorder begin immediately after the traumatic event and need to persist for at least three days and up to one month. When the symptoms persist more than one month, which they invariably do as the lawsuit may take years, the diagnosis changes to posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impairment

The symptoms of depression and trauma carry over into the physician’s home and social life. They can cause impairment, which presents another set of problems. The physician’s spouse or significant other and family are subjected to these symptoms, putting a strain on the relationship. They are the ones exposed to the distressed behavior. Family members are generally the first to suggest there is a problem and that the physician should seek help. When the physician doesn’t talk about the lawsuit at home, either because of shame or other reasons, the connection between the malpractice lawsuit and the physician’s symptoms is not well appreciated. This disconnect sets up a cognitive dissonance experienced by the physician’s family who will then try to search for other causes for the behavior.

Physicians are not good at asking for help for their own medical or mental health problems. Unfortunately, they learn in residency that asking for help is a sign of weakness, and that getting help can have licensure and hospital privilege repercussions. This misinformation only adds to the stigma physicians face when needing help. So, physicians go un-helped and untreated until disaster happens. Many physicians do not have their own primary care provider and get substandard healthcare by using “hallway consults” or by treating themselves. A physician who treats themself is on a very slippery slope to self-medicating with alcohol or mood-altering drugs. This scenario only makes matters worse.

Defense Mechanisms

Physicians are goal-oriented; when they are stressed, they react by working harder, which may be contrary to what a distressed physician actually needs. This is a form of sublimation, a defense mechanism to combat the feelings caused by a malpractice lawsuit. These unacceptable feelings are transformed into the socially acceptable action of throwing themselves into their work. Another defense mechanism is suppression. Physicians can often “suppress” the unwanted and unpleasant emotions attached to the lawsuit while they are working. Unfortunately, many are unable to successfully suppress or compartmentalize these emotions at other times, including their off-hours, family time, or on a much-needed vacation. When they are away from work the emotions caused by the malpractice lawsuit can come spewing out in all directions, causing family members to recoil.

It’s Not Personal

Being named a defendant in a malpractice lawsuit is a difficult process, but there are ways to successfully maneuver through this minefield. Even though it feels like a personal attack -- especially when reading the inflammatory words on the initial complaint -- it’s important for the physician to realize this is a business decision for the attorney and many times for the patient. When working with a physician who is in the midst of a lawsuit, I often quote from Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, “It’s not personal, it’s business.” It is simplistic, but it’s true. Removing the personal assault tends to lighten the emotional response.

Help

There are other “treatment modalities” that can help a physician successfully navigate this process. The first place to turn is their own family. Physicians need to share their emotions with their spouse or significant other. It is amazing how simple this process is and how well it works. The embarrassment can create resistance to talking about the lawsuit but discussing the feelings caused by the lawsuit does reduce the emotional energy it can have over the physician. While they are under legal advice not to discuss details, they can share the emotional experience of the lawsuit.

Other helpful options include practicing a Mindfulness-based meditation program. Mindfulness is an excellent form of meditation that has been shown to promote gray matter changes for the better – and it can help a physician to calm the emotional reaction.

Seeking individual psychotherapy is another solid approach to dealing with the emotions brought on by a malpractice lawsuit. Many therapists are now using telehealth which makes this process even easier to utilize. When starting with a new therapist, I advise giving the therapist three appointments; if by the third appointment there is no trust, comfort, or a therapeutic alliance formed, then go to the next therapist on your list. Your health insurance provider will have a panel of therapists; the TMF also has lists of vetted therapists in Tennessee’s major metropolitan areas.

Another very effective strategy is joining a support group, whether it’s malpractice-focused or one offering general support. There are many types of support groups including gender- specific, trauma-focused, substance use-focused and time-limited, to name a few. Therapy support groups have the same protection as other forms of therapy, meaning what is said in the group is confidential and protected. And it is much more therapeutic for the physician to talk about the emotions they are having, rather than the specifics of the clinical case.

Trust the Experts

It is important to remember when named as a defendant in a malpractice lawsuit that you will be represented by a competent defense attorney retained by SVMIC. Your attorney understands and knows the law and the litigation process, just as you understand your practice of medicine. When discussing the lawsuit with your attorney you may experience a flood of emotions; please remember the heightened emotions are caused by the lawsuit itself and generally not by your attorney. Trust your attorney’s expertise, the same way you want your patients to trust yours.

I Will Survive

Being named as a defendant in a malpractice lawsuit is a unique experience that we as physicians are not trained or prepared for. When this happens to you, please reach out for help. Reach out to loved ones, friends, therapists, and to our staff at the Tennessee Medical Foundation – all of whom are here to help and support you through this arduous process. Keep in mind that in Tennessee, a physician does not have to report to the licensing board that they reached out to the TMF for emotional support. The TMF is here for you, and will help you through this process that, believe it or not, you will survive.

The contents of The Sentinel are intended for educational/informational purposes only and do not constitute legal advice. Policyholders are urged to consult with their personal attorney for legal advice, as specific legal requirements may vary from state to state and/or change over time.